In what would seem like insurmountable odds, six Neosho residents without legal counsel took on the attorneys of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources and MoArk, LLC at a hearing held September 28 and 29 in the U.S. District Courthouse in Springfield with the case yet to be concluded. What the residents, most living within a few miles of the egg-laying facility known as MoArk 7, were attempting to do was to stand up against the MDNR's granting of permit MO-0122840 for the operation and eventual expansion of the MoArk controlled animal feeding operation. The1-A CAFO would sanction as many as 3.6 million chickens in an area currently holding a bit more than a third and the eventuality of producing 135,000 tons of litter annually.

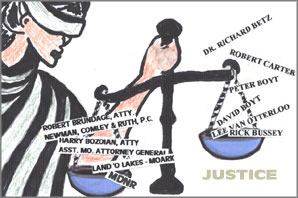

Testifying before Administrative Hearing Commissioner June Doughty were petitioners Peter and Dave Boyt, Rick Bussey, Robert Carter, Dr. Richard Betz and Lee VanOtterloo. Facing them were MoArk's attorney Robert Brundage and in the role as defender of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Assistant Attorney General Harry Bozoian.

The hearing was bogged down from the beginning while the parties discussed who went first. Both of the defendants' attorneys pursued settlement of several legal technicalities before MoArk's attorney presented his motion to quash the entire preceding based upon his interpretation of a rule of civil procedure. It was turned down.

Petitioners' limitations

The petitioners in this case were standing in for about 3600 Newton County residents who had signed a petition circulated by SWMCALME, a group protesting the CAFO expansion. They were proceeding pro se, meaning that they were representing themselves without a lawyer on their side.

The group took no time in summing up the role of Brundage as "to tie our hands and gag us," and admitted that what many of them knew came from watching Judge Judy. Dave Boyt said that it was to their advantage that Commissioner Doughty was a "naturally curious person." Her continuous overruling of the attorneys' motions to exclude testimony represented her desire to facilitate the pro se petitioners although she cautioned them over proceeding with "evidence" not presented during the discovery phase prior to the hearing, in this case a one-sided event in which the defendants took depositions from the petitioners. In addition, Doughty told Brundage that she agreed that his points that documents submitted by the petitioners needed to be relevant to the appeal, but that she needed time to rule on this.

Right off the bat Bussey was not able to bring into evidence a speakerphone conversation he overheard between the former MDNR's Randy Kixmiller (he's now working privately in Chesterfield, coincidentally where MoArk's corporate offices are located) and Newton County Commissioner Jerry Carter during which Bussey alleges that Kixmiller called the MoArk expansion "a done deal" soon after MoArk's construction permit was granted. The sworn affidavit signed by Carter and delivered by Bussey was deemed inadmissible without Carter's presence.

The mysterious disappearance of a subpoena by the St. Louis County Sheriff's Dept. meant for Kixmiller was moot when Brundage's motion to quash the subpoenas was granted after he had proved that the petitioners hadn't included expense checks with their applications. Exhibit 1, Kixmiller's response to petitioners made nine days before the hearing, was submitted into evidence by the defendants, without the petitioners' objections--apparently too early in the hearing for them to know they could contest.

Now on one hand we have Brundage defending permitting requirements and Bozoian defending the MDNR by calling the new facilities "state of the art" (we are "so happy with the new design and efficiency"), on the other hand we have a group of citizens knowing that their lives will be impacted by the expansion but not knowing exactly how to prove it. Bussey, calling himself a guinea pig because he was the first petitioner to take the stand, showed obvious distress over having to abide by legal procedure for, as he said, "trying to get the truth out."

The commissioner tried to warn the petitioners early on that any allegations they make must be backed up by facts that are subsequently put into evidence by competent witnesses, but competent witnesses demand a hefty fee before testifying, something the six thought they could avoid. So, even though they knew that the air drying litter method the defendants' lawyers were calling "state of the art" was being tossed out in Europe where it had been initiated years ago, they had no way of bringing that fact into evidence.

The testimony of Dr. Betz, a retired internist, was cut short by Doughty when he attempted to show that CAFOs cause health problems. He couldn't directly equate any health problems with MoArk based upon his own experience. And even if he mentioned that he had to dig his well deeper a couple of times, he wouldn't be able to equate it with MoArk's well-digging activity. Missouri is a riparian state that does not regulate the use of groundwater, as Brundage was quick to point out. Betz did offer MoArk's past history of violations into evidence documenting their past contempt for clean water laws, but without appropriate testimony and the DNR's ruling that past history played no part in the permitting process, this evidence might just be taking up space.

VanOtterloo created a map using Google attempting to prove that because the property of Betz, Peter Boyt and Bussey fell within a 4500 ft. radius, according to DNR's own regulations, they had to have formal notification, which they didn't, before the operating permit was issued. The map was accepted by the commissioner as a "demonstrative" exhibit, but she implied that an experienced cartographer had to show its relevance.

MDNR employees testify

Camille Dobler, an air inspector for the MDNR, was Bussey's first witness. He tried to get her to admit that a vegetative buffer mandated by the permit for odor control was not properly in place and that odor sampling wasn't done on a regular enough basis, but it took the commissioner's intervention to get Dobler to admit that things needed to be addressed regarding MoArk's odor control plan. At one point Dobler's silence suggested that she had no idea who sets requirements for odor enforcement nor determining the effectiveness of self-monitoring considering MoArk's having given themselves perfect scores. Bedrosian tried to clarify that the permit required an odor control plan and that MoArk had one. Period. And no mention was made of the possible lack of experience or the poor calibration of the equipment to be used by the students of Missouri Southern State University assistant professor, Mike Kennedy who were chosen for a planned eventual six-months air monitoring study.

David Allison, an environmental specialist for the MDNR who supposedly responds to odor complaints in Southwest Missouri but who testified that he didn't "do much air stuff," was called by Bussey allegedly because Allison had told him that he had to remove his clothes after having taken an odor sample. Allison denied this on the stand even though he admitted to finding that an area on Camp Crowder property directly north of the Farmer Automatic Building (FAB), or composter of raw manure, was "stinking really badly." Continued operation of the composter that allegedly is accepting raw manure from MoArk's Anderson farms is a major concern of the petitioners.

The testimony of Leanne Tippett Mosby, MDNR deputy division director, seemed to point up the lack of organization within the agency. Tippett Mosby, a former air pollution control enforcement agent, on the stand was unable to judge the effectiveness of the odor control plan nor its enforcement--although she did admit that an enforcement standard should "take compliance history into account". She passed the buck back to Dobler, saying she would be the one to provide an assessment of how MoArk is abiding by the plan through her inspection. As a "director, Tippett Mosby often offered vague testimony. But when Carter said that her agency could be responding to complaints on a more timely manner, Tippett Mosby blamed those limitations on lack of personnel, an often heard excuse made all the more incredulous to the petitioners considering the number of unnecessary employees they thought were sitting in on the hearing.

Bussey wanted a definition of what Tippett Mosby considered an "odor nuisance". Her response was that although it was impossible to regulate odor as to definition, an odor was a nuisance when it "unreasonably interferes with the enjoyment of life or the use of property." However, she clarified that a work group within the MDNR had determined that Highway D that transects MoArk property was an inappropriate place to monitor for odors. Therefore, a traveler's enjoyment of life had to wait until after he or she passed that area.

The effect of the odor

A notarized letter from James B. Tatum, president of the Crowder College Board of Trustees and Alan D. Marble, Crowder's interim president presented for evidence by Pete Boyt was deemed inadmissible and not a substitute for their presence so that they could be cross-examined, another legality of which all the petitioners were unaware. The letter was an attempt to bring into evidence the negative effect MoArk has on the college campus within proximity to MoArk 7 Farms.

Despite Brundage's incredulous stares, Doughty, however, gave Pete Boyt the opportunity to state how MoArk impacts him. Pete, who lives about one mile south and east of the proposed MoArk expansion said that at times the odor is so bad that he can't go outside to work, that the clean smell of clothes drying on the line has been replaced by the smell of chicken litter, that his spring-fed well is now contaminated with e coli, that because of MoArk's litter application Hickory, Indian and the Elk River were waterways he was unwilling to swim in or float on, and as a replacement for the Tatum/Marble letter, that a heavy odor during many evening performances at Crowder causes attendees to leave early after the smell permeates the buildings.

Proceedings are expected to continue on October 12 and 13 with more witnesses called up by the petitioners. Currently, Doughty is looking for a suitable place to hold the hearing since the courtroom they used would be unavailable.

Comments