"The problem is we don't have a family doctor since we're almost never sick," Samuels tells his wife Rikki in answer to her suggestion to seek medical attention. Luckily, his wife's doctor responds to his message left with her answering service and suggests he immediately get himself to the nearest ER, at Nyack Hospital, where a stand-in for her will examine him.

Before Dr. Howard Long's arrival, Samuels says he is examined by the ER doctor at the end of his long shift. This doctor wants to send him home without having paid the slightest attention to the brief history he has provided. Fortunately for Samuels, Long, assisted by a neurologist on duty, arrive and find significance in his having been inoculated for his visits to a couple of Third World countries just a month prior and that he had experienced symptoms of a bacterial infection after returning home. Their suspicions lead them to a tentative diagnosis of Gullain-Barr syndrome, a mysterious but serious autoimmune disorder that could follow a minor infection.

Frightful of the spinal tap that his doctors order to make a diagnosis, Samuels attempts to stop them but realizes that he has no option, that his ignorance of medical treatment is vast. Consequently, he doesn't question their decision to hook him up to a respirator for problems "later on." Unfortunately, the procedure is worse than its presumable outcome and Samuels is flooded with mucous from the respirator tubing as well as a nasal feeding tube, putting him for the first time at the mercy of attendants who prove to be either roughly mechanical or less than competent in relieving him.

While no obvious treatment towards a cure is begun at Nyack, Samuels' condition worsens. Page by page the reader of Blue Water, White Water (Up the Creek Publishing, 2011) is introduced to what he is thinking, to his brief tangents set in italics that introduce a life well lived, but mainly to the horrors worsened by his ability to do nothing more than blink to communicate to his caregivers whom, he believes, make him feel less than human or one step closer to the grave.

Samuels gains some hope that someone might try to treat the problem after an associate tells his wife the name of a specialist dealing with Gullain-Barr. Dr. Nigel Ramsbotham, a neurologist at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, wants to try using plasmapheresis, an experimental treatment at the time but one that must be started early on. Samuels' early description of Ramsbotham as someone who seems to be less enthusiastic over the treatment's outcome but more excited over his opportunity to treat a severe case of the disorder is a foreshadowing of events to come.

The reader can't help but suffer along with Samuels as he describes the ambulance ride to the new hospital. He is a man who must be moved from one position to another to lessen intense pain and here he is on a torture ride of a lifetime as he is told he can't be moved.

"I'm fantasizing about Columbia-Presbyterian, imagining rows of beautiful rooms, each looking out at the Hudson and the George Washington Bridge," Samuels writes. "This is New York, the big leagues. All the nurses are friendly and coolly professional. All the doctors are sane. Best part of all, every twenty minutes teams of attendants go from room to room, turning patients."

Unfortunately, Samuels rosy description is no more than a dream. He describes his new room as "ugly as can be." And the first thing his wife is told is that she needs to hire private duty nurses. The stories Samuels eventually tells about them are a book in itself. Questioning whether the nurses are screened, Samuels writes, "We're in a trap, paying a hundred dollars a shift for these nurses...Pearl is dangerously incompetent, Ida is brutal. And Ingrid, the best of the lot, is a neurotic, man-hungry, immature slob. Does anyone screen these women? Does the hospital take any responsibility for seeing that they are qualified?"

Samuels describes Ramsbotham as a "British eccentric right out of a loopy comedy." Even though his son Charlie visiting from college--to whom we were introduced earlier as one who thankfully massages his father's legs--tries to pin the doctor down on when he would start treatment, Ramsbotham, the reader is told, evasively answers, "very soon." This response turns into "happening only at the insistence of family" and then, is too late.

Writes Samuels about Columbia-Presbyterian: "At Nyack I was in an open ward. Other nurses could see me. Here I'm in a room, out of view. At Nyack I was wired with sensors that sounded alarms if anything was wrong. the only alarm I have now is in the respirator. What happens if my heart stops? Will anyone know? Will anyone care?"

And what does being in a new hospital mean? Everybody knows that hospital staff seize upon the opportunity to take new x-rays, do repeat tests--a second spinal tap to confirm Nyack's diagnosis?-- or order new ones. The description of Samuels suspended in the air when his Ramsbotham-ordered bed breaks down is a bit of black humor, especially when staff won't take him out of it without doctor's orders.

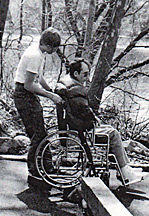

Son Charlie is shown wheeling his father around the yard of their new house after it was determined that the house they had lived in could not be made wheelchair accessible. (Photo by Sally Savage)

Son Charlie is shown wheeling his father around the yard of their new house after it was determined that the house they had lived in could not be made wheelchair accessible. (Photo by Sally Savage)

Samuels doesn't go into great detail over his transfer to Helen Hays Hospital and later to Rusk Institution of Rehabilitation Medicine although he does describe Helen Hays Hospital as being a very depressing place, with questionable hygiene, spotty rehab sessions and abominable food. His experience at Rusk includes a bout with pneumonia after a too eager doctor pulls out his tracheotomy tube.

Most of the book, Samuels says, was written in the 1980s when his memories were fresh and his anger highest. He can't say if he were a patient today in the same hospitals whether his experiences would be the same, but he does leave the reader with the advice to never assume that doctors and nurses don't make mistakes. Be your own advocate or have someone act on your behalf, he cautions.

Title - Blue Water, White Water

Author: Robert C. Samuels

Publisher: Up the Creek Publishing (Nov. 15, 2011), 304 pp.

$11.95 (paperback) at amazon.com

ISBN-10: 0984019413 /ISBN-13: 978-0984019410

Comments